On Augustine's Treatise Concerning the Correction of the Donatists

The origins of the Donatist controversy are to be

found in the Diocletian persecution of the early fourth century, during which

many clergymen surrendered “sacred books” under duress. This would prove to be the final imperial

attack on the Church, as the persecution of Christians within the empire was

brought to an end with Constantine’s “Edict of Milan” in AD 313.[1] The issue began with the disciples of one Donatus

moving to have him consecrated Bishop of Carthage that same year,[2] as

the rival of Caecilianus, who – so claimed the Donatists – had been consecrated

two years earlier by a Bishop who was a “traditor” (i.e. “surrenderer” of

sacred Scripture), thus nullifying Caecilianus’ episcopal consecration (cf. Treatise

1.5). The Donatists contended that those

clergy who had proven themselves unworthy during the persecution were not only forbidden

to return to their ministry, but also that whatever sacraments they had

performed had been rendered invalid due to their capitulation to imperial

pressure. The Donatists taught a form of

“perfectionism”, i.e. that Christians should strive to attain perfect holiness

during this life and that the (true) Church consisted of, not all the baptized,

but only those who demonstrated their godliness.[3]

A number of

factors contributed to the Donatists’ success as a distinct Church in North

Africa – both the fact that they were in the majority for a long time and that,

until 398, they enjoyed the support of Gildo, a local ruler who cultivated a

kind of semi-independence from Rome.[4] Augustine’s ascendency to the episcopacy[5]

coincided with the imperial overthrow of Gildo and from that point on – in an

ironic twist of fate – the empire, with Augustine’s theological backing, would

repress the Donatists and “compel” them to conform to the dictates of the

“Catholic Church”, i.e. the Church sanctioned and legitimized by the empire.[6] For better or for worse, the die of Western

theology was cast[7]

during this portentous time of the “establishment” of the Church, and it was

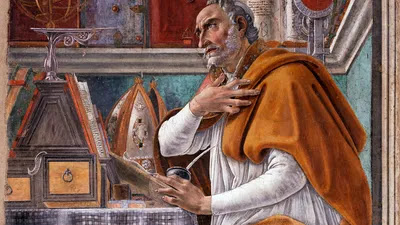

cast by Augustine[8]

(354—430).

Augustine

wrote his Treatise around five years after having given his approval to

the imperial repression of the Donatists.[9] From the outset, we are witness to

Augustine’s equating the Church with the kingdom of God; to that effect, he

quotes passages from the Psalms and Luke’s Gospel which describe God’s action

vis-à-vis “the nations”. One might say

that Augustine has a (overly-)realized eschatology, as he uses the Scriptural

testimony to God’s desire to reconcile all nations with the activity of the

Church in league with imperial authority to demonstrate that the

ecclesiology of the Donatists is (literally) heretical. Applying (the messianic) Psalm 2 to Caesar is

to say that the victory of the Roman empire is the victory of the divine

kingdom (or at least, the Church).[10] In the Treatise, we see a facile

identification of ancient Israelite kings with “godly” Caesars, both of whom

enforce divine justice (cf. 5.19).[11]

Augustine’s

denunciation of Donatist atrocities in chapter 3 strains credulity and smacks

of vindictiveness (cf. 7.26-27). The

comparison between, on the one hand, the accounts of the Donatists’ “suicidal

proclivities”, which are admittedly based on hearsay (3.12) and yet eagerly

transmitted by Augustine, and, on the other, his refusal to countenance

second-hand reports “from the enemies” of Caecilianus according to which he had

been consecrated by traditores (cf. 1.5), is telling. Surely, the Donatists are worthy of the same

benefit of the doubt as Caecilianus?

Augustine makes a mockery of the Donatists’ eagerness to experience

martyrdom, dismissing them as suicidal madmen under the influence of Satan (cf.

3.14).[12]

In chapter

9 of the Treatise, Augustine’s argument reaches a kind of climax, as he

provides the ultimate theological vindication for the imperial measures being

taken against the Donatists – there is no salvation (justification) apart from

the (Catholic) Church (9.40)! In this

chapter, Augustine repudiates the Donatist notion of a “pure” Church and

insists that the Church will only be found to be “without spot or wrinkle” at

the eschaton. There seems to be some

inconsistency in that Augustine seems content to allow “the tares to grow

alongside the wheat” as long as they are growing within the confines of the

Catholic Church! Better a wicked

Catholic than a righteous schismatic…

Augustine is content to await the eschaton for God’s judgment as to

whether people are “ultimately saved” but is unwilling to brook any delay when

it comes to “correcting” present resistance to the ecclesial-imperial order.

In chapter

10, Augustine addresses himself to practical issues that may arise should

Donatist clergy seek to come back into the fold. Augustine insists that even those priests who

were ordained by Donatist bishops should be permitted to maintain their

ecclesial rank and privileges upon returning to communion with Rome. This is consistent with the strand, found

throughout the Treatise, of the blend of mercy and judgment when it

comes to church discipline. Augustine

does often come across as very “pastoral” and takes pains to point out that the

imperial authorities have often shown forbearance in their application of the

anti-Donatist legislation (cf. e.g. 7.25-26).

Then again, Augustine doesn’t hesitate to set up

Donatist/Circumcellionian barbarism as a foil against which to portray the

enforcement of imperial measures as being “right and just”. In the final chapter, Augustine seeks to

allay Donatist fears that they have committed “the sin against the Holy Spirit”

by their heresy. Augustine affirms that

the infamous “blasphemy against the Spirit” of which Jesus warned his

contemporaries (Jews) consisted in their refusal to believe in him.

At the end

of the day, in this Treatise, Augustine comes across as a Pastor

(Bishop) concerned with the physical safety of his flock (cf. 7.25, and the

closing sentence of that chapter), the unity of the “universal” Christian body

and the well-being of the empire that had proved itself surprisingly generous

towards the Church. Perhaps there is

something of the spirit of Jeremiah’s “pray for the city to which I have sent

you” in the Treatise (cf. Jer. 29.7).

Also, Augustine must have been apprehensive as he contemplated the fate

of the Church in a not-too-distant future when she would no longer benefit from

imperial protection but would be obliged to negotiate the terms of her

existence with the “pagan hordes”.[13] Indeed, Augustine’s lifetime was

characterized by the imperial patronage of the Church, situated as it was

between the time of persecution and that of the barbarian invasions. This Treatise fully reflects

Augustine’s historical and pastoral reality.

Naturally, Augustine

would be interpreted by the medieval Church as underwriting the (then)

all-encompassing power of the Church/bishops of Rome, even to the point of Popes

both establishing and deposing monarchs.

Closer to home, perhaps reading Augustine in our “secular age” could

serve to encourage prudence when it comes to seeking government support for

Churches. Proponents of Christian

Nationalism[14]

seem to aspire to a situation not too far removed from that of Augustine’s

day. However, in today’s multicultural

and pluralistic environment, it is difficult to see how an Augustinian approach

to religion and politics could possibly improve the public life of western

nations as opposed to simply exacerbating existing tensions. One should also be wary of playing on fear

(of war) to impose policies that may lead to the oppression of the

“other”. The Church is indeed “Catholic”

in the sense that it is composed of people from “all nations” (so important to

Augustine!). The Church catholic should

lead the way in matters of reconciliation and the fostering of peace and

justice for all people(s).

[1] What a

difference two centuries can make! From

Athenagoras’ Apology for Christians in the late 2nd century

to Augustine’s Treatise Concerning…the Donatists in the early 5th

century, we witness a move from the Church being a misunderstood, persecuted

and powerless entity, pleading with Caesar for the right to exist to a state of

affairs where the (Catholic) Church has the full backing of imperial Rome. Christendom had come! Indeed, the Donatist controversy bridges

these two periods of the emerging Church – from the era of (sporadic) imperial

persecutions, culminating in that of Diocletian (reign: 284—305), to that of

the imperial Church which resulted from the policies of Constantine (306—337)

and Theodosius (379—395).

[2] Some 70 years before Augustine’s conversion in 386.

[3] Another

historical parallel that could be drawn is that of the 17th century

Puritans in England who desired a Church of “the godly” as opposed to one

constituted by the English Monarch and the episcopacy, which emphasized

“sacramental” belonging as opposed to a demonstrable, personal commitment on

the part of believers to a (Reformed) creed.

[4] Cf. Diarmaid

MacCulloch, Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years, London:

Penguin Books, 2009, p. 304.

[5] Of the See

of Hippo, in modern Algeria.

[6] Lest one

get the impression that the Catholic Church at this time was the inexorable,

monolithic force which brooked no opposition that it would later become, one

must recall that the triumph of Christian Orthodoxy was far from being a

foregone conclusion at this stage. The

first Ecumenical Councils were taking place at this time – Nicaea in 325,

Constantinople in 381, Chalcedon in 451 – as emperors and bishops attempted to

unify the Christian population within the empire. Arius, whose beliefs were condemned at

Nicaea, would continue to have influence long after the end of the council

convened to anathematize him. Since some

subsequent emperors would turn out to be arian, the “official position” of the

Church concerning the nature of the Son of God could have gone either way. This was a period fraught with not only

theological division within the Church, but also with the decline and eventual

collapse of the Western Roman empire. (Indeed,

even as Augustine writes to Boniface, “the enemy is at the gates”; cf. Treatise

1.1. Was Boniface perhaps involved in

the repression of the Donatists?? Cf. Ibid. 11.51). Taking this backdrop into consideration helps

one understand the acute impulse felt by people such as Augustine to fashion a

unified Church that could withstand the crises of the times, though one may be

forgiven for believing that Augustine was ready to achieve said unity at any

price, even “against the will” of dissidents such as the Donatists, teaching as

he did that temporal punishments/correction could produce eternal fruit (i.e.

salvation). The spectre of heresy trials

and of stakes planted in mounds of tinder quickly arises…

[7] The

Augustinian mold would not be broken for over a millennium, and perdures still

in many places.

[8] Like many theologians, Augustine was “compelled against his will” to

become a pastor: Diarmaid MacCulloch, Christianity,

p. 304. He was made (coadjutor) Bishop

in AD 395.

[9] Ibid.

[10] At the

time he wrote his Treatise, Augustine was engaged in composing The

City of God. His argument about the

nature of the Church is much more nuanced in his magnum opus; however,

the close identification of the Church with the kingdom of God remains; cf.

MacCulloch, p. 306.

[11] Cf. 8.32

where Augustine draws a parallel (one of many!) between the emperor’s crackdown

vs. the Donatists and David’s crushing of Absalom’s rebellion.

[12] Indeed,

Augustine is one of our earliest sources for the idea that suicide is an

unforgiveable sin. Cf. https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2019/09/29/saint-augustine-contra-suicide/

(accessed Sept. 26, 2024).

[13] Augustine died in 430 during a

siege of Hippo by the Vandals, shortly before the overthrow of the last emperor

of (the city of) Rome.

[14] Concerning

Christian Nationalism in the U.S.A., there is irony in the fact that many of

the first “Americans” came to the new world to escape the oppression of the (established)

Church of England.

Comments

Post a Comment