GOD'S NEW WORLD, DAY 34 (how to conquer the world)

A Divine Revolution. In

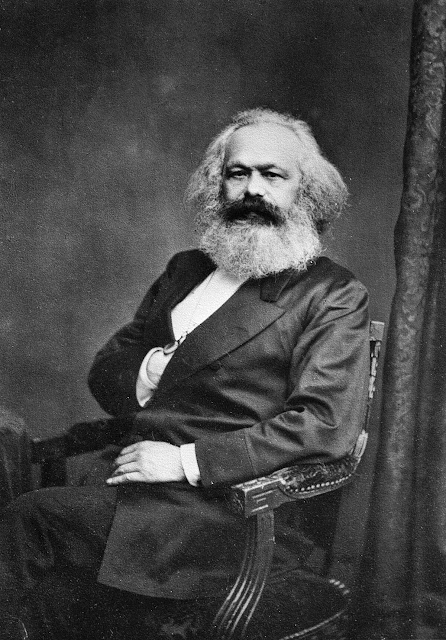

their Communist Manifesto of 1848, Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels said:

“The

Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that

their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing

social conditions.

Let the ruling classes tremble at a communist revolution.

The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains.

They

have a world to win.

Working Men of All Countries, Unite!”

While the connection between the creators of communism and the book of

Revelation might not be immediately obvious, make no mistake! Revelation is a book about a revolution

and a dream of a new world where there will truly be justice for all. Revelation has been misunderstood,

domesticated, and reduced to a “Christian cosmic horoscope”. Strangely, Revelation has often been put

forward as providing a vision of “the great escape” from the world into “eternity”,

“heaven”, call it what you will. Perhaps

this is because many readers run out of gas before they get to the final chapters

of the book. The fact remains – Revelation

(and thus the Bible) does not end with the annihilation of the world and

a neat separation of believers and unbelievers into their respective eternal accommodations

– be it hell or heaven. So how does Revelation

“end”? Revelation ends with a vision of

a new world, “a new heaven and a new earth”, with the new Jerusalem descending

from heaven to become the center of the life of the inhabitants of this new and

intriguingly strange world. In other

words, the final chapters of Revelation show us that the Creator’s plan has not

changed. “In the beginning, God created

the heavens and the earth” (Gn. 1.1) and in the “end”, God re-creates the heavens

and the earth, with human beings inhabiting, not heaven, but the new

earth. These facts risk altering the shape

of our theology, our understanding of the Christian life…in a word, everything. Indeed, Revelation is a book about everything

– about God, the world, the past, present and future, about power, justice,

truth and violence. All the big themes which

are the subject matter of a liberal arts curriculum are to be found in Revelation.

So, what exactly is the nature of the revolution that we find in

Revelation?

“The

kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah, and

he will reign forever and ever” (Rev. 11.15).

There it is – Revelation is a book about a

regime change. The world is going to be under

new management. No longer will “worldly”

powers rule the earth; Revelation dreams of the moment when God will rule his

world without any rivals claiming divine prerogatives or usurping the Creator’s

authority. This verse is the ultimate

anti-imperial statement. Ever since the failed

construction of the Tower of Babel, humans – so the Bible tells us – have attempted

to consolidate power and rule the world by establishing empires and conquering,

subjugating, and absorbing as many “nations, tribes, peoples and languages”

(cf. Rev. 7.9) as possible in a vain attempt to unite humanity through coercion.

The Kingdom of the World. In

Gn. 1.26-31, God created human beings in his image in order that they may “have

dominion” over his creation. Human

beings mediate the Creator’s authority in his world. Psalm 8 picks up this theme and says that God

has “crowned mankind with glory and honour” (Ps. 8.3-8, esp. v. 5) – the glory

of God is manifested when human beings exercise their God-given mandate to

“rule” over creation. One way to

summarize human history is in terms of humans presuming to “rule” over the world

(through civilization and empire) without reference to the Creator but rather,

through the amassing of power, setting themselves up as “gods” with

prerogatives which rightly belong only to the Creator.

Babylon. Indeed, Yahweh –

the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob – is consistently shown in Scripture to be

anti-imperial. The Creator’s campaign

against evil was launched following the blatant display of hubris which

consisted of the construction of the Tower of Babel (=Babylon: Gn.

11.1-9). Following this failed attempt

to establish a memorial to human arrogance, Yahweh called Abram to leave the

civilized comfort of Sumer/Babylonia (the very cradle of civilization) and to

become a nomad, called to “go” to an-as-yet-undisclosed destination (Gn.

12.1-3). Abra(ha)m and his extended

family eventually settled in Canaan (the Levant), and three generations later,

due to a famine, the family’s fate would become entwined with the other major

civilization of the Ancient Near East – Egypt.

Egypt. It is in Egypt that

Abraham’s descendants fall victim to the dark drives of empire – provoking

Pharaoh’s fear as an ever-growing ethnic minority, the “Hebrews” are enslaved

for 400 years. Finally, Yahweh hears the

cries of his oppressed people (cf. Ex. 3.7-8) and sends Moses back to Egypt to

deliver the people of God. During a

protracted struggle – enacted “in heaven” between Yahweh and the gods of Egypt

and “on earth” between Moses/Aaron and Egypt’s sorcerers/Pharaoh (himself

believed to be the embodiment of Ra, the Sun-god[1])

– the Egyptian empire is subjected to a series of humiliations, culminating in

the “exodus” of the Hebrews (cf. Ex. 3—15).[2] So, already in the first two books of the

Bible, the God of Israel has set himself against the pride and domination of

empire – whether it be that of Babylon or Egypt. The people of this God (i.e., Israel) are

called to demonstrate a radical alternative to empire – they are to be a tribal

confederation on the march to the Promised Land, led by a prophet (Moses) and

living under the rule of Yahweh, the truly divine king.

Rome. In the first century

(AD), the “kingdom of the world” was the empire of Rome. Like all empires, Rome wasn’t big on

humility. Roman imperial propaganda boldly

proclaimed that with the rise of Rome, humanity had “come of age”. Roman civilization was the summit of human achievement;

Rome had “pacified” the world and ushered in an age of justice and peace. Indeed, the “glory of Rome” was the

manifestation of the divine will – the gods had chosen Rome to rule the world

and manage humanity. The Roman empire

had established a new status quo – a state of affairs that was not only

considered to be “normal”, but was presented as being praiseworthy, as

something that any reasonable person should aspire to emulate and that promised

rich rewards to those ambitious souls who would serve the imperial order (and

thus serve themselves). Of course, no

need to mention the embarrassing fact that this glamourous empire had been

built on the backs of slaves and continued to exploit the nations that it had conquered

by robbing them of their resources and funneling the wealth of the world back

to the imperial capital. Alas, this is

the way it has always been – humans “rule” each other by means of domination,

exploitation, and brute force (cf. Mk. 10.42) – or perhaps nowadays in some places,

people get to vote for those who have managed to finance their candidacy and

campaigns, yet always with the rhetoric that it is all for the “common good”.

Behind enemy lines. It is

uncanny that Jesus was born during the reign of the first Roman emperor (Lk.

2.1). Once Octavian had defeated

Mark-Antony and consolidated his rule, there was no republican pretence left –

Rome had undeniably become a global empire under the rule of one man –

Caesar “Augustus”, Julius Ceasar’s adopted son and heir (as Octavian has become

known to history). As the greatest empire

the Western world had ever known was coming into its own, believing itself to

be the apex of human potential (as well as pride and injustice), the Word of

the Creator became flesh (cf. Jn. 1.1, 14) in an imperial backwater – the province

of Judea. The divine revolution was

underway. Whose dream for the world

would come true – Caesar’s or the Creator’s?

Who was the Lord of the earth – Caesar or Christ? Whose kingdom would unite the peoples of the

world in truth, justice and peace – Rome’s or God’s? The stage was set for a showdown. The Romans did not take resistance to the

imperial order lightly, and those perceived as a threat to that order were always

dealt with, often savagely. Enter “John”…

A first-century revolutionary.

The book of Revelation begins with “John” introducing himself thus:

“I,

John, your brother who share with you in Jesus the persecution and the kingdom

and the patient endurance, was on the island called Patmos because of

the word of God and the testimony of Jesus.” (Rev. 1.9)

John is in exile on an island off the

coast of what is now western Turkey in the Aegean Sea. He is experiencing “persecution” because of

“the word of God and the testimony of Jesus”.

His audience consists of 7[3]

local Christian communities in the Roman province of “Asia” (1.10-11). John does something interesting right from

the get-go – he identifies the members of these “churches” with the people of

God going all the way back to the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt (Rev.

1.4-6; cf. Ex. 19.5-6). John is drawing

a deliberate parallel between the ancient Israelites and his audience – they

have been (will be) delivered from an empire that had dominated them in order

to become a “kingdom of priests” for the one true Creator-God (i.e. God will

rule his world through them; cf. Rev. 5.9-10).

This signals the central theme of the book – the Creator is establishing

a kingdom in the midst of his world, a kingdom that will displace all earthly

empires, i.e. all those who have usurped the authority of the Creator (cf. Rev.

11.15).

Our Lord and his Anointed.

Indeed, conflict between the “kingdom of the world” and the “kingdom of

God” is nothing new. The second Psalm is

one of the favourite Psalms of the New Testament, i.e. it is often quoted by

the NT authors. Psalm 2 describes “the

nations” and “the kings of the earth”[4]

who plot against Yahweh and his anointed king in order to liberate themselves

from their rule (Ps. 2.1-3; cf. Rev. 1.5, 11.15). This Psalm reflects, perhaps, the situation

of the kingdom of Israel during the reign of Solomon[5]

(cf. 2 Sam. 7.12-16) when Israel’s territory had expanded to include several

surrounding nations and when rulers came from far and wide to pay tribute to

Solomon in Jerusalem (cf. 1 Kings 4, 10).

In response to the conniving of the pagan nations, Yahweh – the “one who

sits in the heavens”[6] (Ps. 2.4)

– laughs and castigates these rebellious Gentile rulers in his wrath[7]: “I have

set my king on Zion, my holy hill” (2.5-6).

Yahweh then turns to his anointed, the king of Jerusalem, and tells him:

“You are my son[8]; today I

have begotten you” (2.7)[9]. Yahweh continues to speak to his “son”: “Ask me,

and I will make the nations your heritage, and the ends of the earth your

possession” (2.8). The aspiration

reflected in this psalm is that Yahweh, the king of the cosmos (cf. Pss. 47,

93-99), will rule over the nations of the earth through his viceroy, the king

of his people, Israel. This is the Old

Testament vision of the “kingdom of God”, which displaces all earthly kingdoms

(with the exception of Israel: cf. Dn. 2, 7).

After promising the insubordinate nations to his earthly representative,

Yahweh instructs his anointed to “break them with a rod of iron, and dash them

in pieces like a potter’s vessel” (Ps. 2.9).[10] The psalm ends with a solemn warning to the

kings of the earth to submit to Yahweh (i.e. his representative in Zion: Ps.

2.10-11; cf. Rev. 1.5) and thus avert his wrath.

The world’s true Lord. The

New Testament naturally understands Jesus as having fulfilled Psalm 2. To look no further than the two-volume work

of Luke-Acts: the birth of the Davidic “son” of God is announced (Lk. 1.30-35) “in

the days of Caesar Augustus” (Lk. 2.1) – who also claimed the honorific “son of

a god”[11] – the Son

of Yahweh/anointed king of Israel (i.e. Messiah) is eventually attacked and

killed by “the kings of the earth” (Lk. 23; cf. Ac. 4.25-26), but is raised

from death (Lk. 24; cf. Ac. 2.24-28, quoting Ps. 16) and endows his apostles

with a mission to “the ends of the earth” (Ac. 1.8)[12]

before he is elevated to “the right hand of God” to reign over the cosmos as

Lord[13] of the

nations (Ac. 1.9-11; cf. 17.6-7). The

“kingdom of God” had been the main subject of Jesus’ teaching (cf. Lk. 8, etc.)

and serves to bookend the book of Acts (Ac. 1.3; 28.30-31).

Indeed, Psalm 2 provides the theological justification for everything

the apostles undertake in the book of Acts (besides the explicit instructions

given to them by the risen Jesus in chapter 1).

If Jesus is the Messiah of Israel, then he is also – so says Psalm 2 –

the lord of all the nations, and the envoys of the Davidic king therefore

travel to the ends of the earth with the “gospel”[14]

(royal proclamation) that the world’s true ruler has acceded to the throne of

the cosmos. The kingdom of Yahweh is

thus established among the doomed kingdoms of the earth (result: “the world is

turned upside down”: Ac. 17.6).

Subversive cells. And so,

the early Christian missionaries had planted pockets of resistance to the

imperial order all over the Eastern part of the empire – and even in Rome

itself! The early churches were small communities

of people loyal, not (primarily) to Caesar, but rather to Jesus. Among these dissident “cells” are “the 7

churches of Asia” to whom John sends the book of Revelation. John, who is writing “from prison” as it

were, who knows that his life could end at any moment, wants to remind his comrades

of the Creator’s dream, the dream of a world remade, a world of which their insignificant,

apparently powerless communities are the beginning. The 7 churches of Asia are God’s bridgehead as

he seeks to reconquer his world from Caesar, his legions and his monstrous

imperial apparatus (cf. Rev. 13). John

calls his readers to a life of resistance.

They must not give in to the pressure to conform to the imperial way of

life! They must remain loyal only to Jesus,

even at the cost of their lives – just as their Lord had done.

As C.S. Lewis put it in Mere Christianity:

“Christianity

[believes] …that this universe is at war.

But it does not think this is a war between independent powers. It thinks it is a civil war, a rebellion, and

that we are living in a part of the universe occupied by the rebel [i.e.

Satan]. Enemy-occupied territory – that

is what this world is. Christianity is the story of how the rightful king has

landed, you might say landed in disguise, and is calling us all to take part in

a great campaign of sabotage.”

A paradoxical Revolution. Unlike

the various Communist revolutions of the 20th century, during which

the revolutionaries massacred millions of their opponents – it is precisely by

dying for their faith that the members of the 7 churches of Asia are called

to “conquer” the “beast”, the “world” and all the enemies of God. Jesus showed us the way to true victory – by

giving up his life on the cross, he defeated the “principalities and powers”

(cf. Col. 2.14-15). Despite the fact

that everyone – including the disciples – believed that Jesus’ death was a

defeat and proof that he was not the Messiah after all (cf. Lk.

24.19-24), the New Testament consistently insists that the opposite was in

fact the case. The cross was Jesus’

“enthronement” as Messiah, as King of Israel, and constituted his victory over

the true enemies of the people of God – sin, death and all the forces of

evil (cf. Eph. 6.12). The New Testament

tells us again and again, lest we miss it – the kingdom of God is an

upside-down kingdom. That is to say,

God’s powerful reign functions in the opposite way from human

regimes. For God, true power is

manifested in weakness, humility, suffering, humiliation, service – yes, even

death (cf. Lk. 1.51-53; Mk. 10.42-45; 2 Cor. 12.10). Humans “do” power motivated by fear and

pride; God does power by humility and self-giving love (cf. Phil. 2.5-11). That being said, it takes a lot of courage to

follow Jesus on the path of the cross and of self-denial (cf. Lk. 9.23); it

requires bravery to trust God, to render oneself vulnerable to attack,

rejection, and mockery instead of defending one’s rights and status. We are members of Jesus’ subversive kingdom,

called to “fight” with the “weapons” of compassion and service. As those who are – according to the world’s

standards – powerless (if they only knew), we are called, not to escape

this world – or indeed, suffering for our faith – but rather to engage

our world (even those who are hostile to us) with the love of God, which is

more powerful than hatred, violence and all devices that humans can conjure.

Modern martyr. A

relatively recent example of just this kind of courageous discipleship is that

exemplified by Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906—45).

Bonhoeffer was a young German pastor/theologian who was invited by

friends to escape trouble by going to the U.S.A. once Hitler came to power in

Germany. Bonhoeffer initially accepted

the offer, and was warmly welcomed in America and was offered many opportunities

to teach in seminaries and publish books – in short, to become a theological

sensation. However, as he enjoyed the safety

of America, Bonhoeffer was tortured by the thought that he had abandoned his

nation at the moment when she needed him the most. Finally, after a few months in New York, he

decided to return to Germany and face whatever fate awaited him. He went home, joined a “coalition” of

“confessing” churches who refused to swear allegiance to Hitler (the National

Church of Germany, known as the “German Christians”, had endorsed Hitler),

founded an underground seminary to train leaders for these dissident congregations,

continued to write theology, and even worked as a double-agent, feeding

information to British operatives through his activities as an agent of German

military intelligence. Eventually, his

involvement in the Valkyrie plot to assassinate Hitler was discovered, and he

was imprisoned by the Gestapo and eventually hanged on April 9, 1945, just a

few weeks before the end of the war.

Bonhoeffer had only recently turned 39 years old. What a clear example of following Christ

courageously on the way of the cross!

Bonhoeffer turned his back on personal prestige, comfort and safety and

deliberately chose to do the hard thing – to go into the lion’s den and serve

Christ in the midst of an extremely traumatic time in Germany’s history, where

fear was rampant and the temptation to be co-opted by the Nazi regime was all

but irresistible. Bonhoeffer lived

the book of Revelation. In the face of

seemingly insurmountable odds, when it must have felt like everyone was against

him, he served Christ and the gospel, resisted the pressure to conform to the

demands of a demonic regime, and took the consequences. Bonhoeffer overcame; he triumphed.

A call to bold engagement.

I put it to you that this is how we should read the book of Revelation –

not as an invitation to escape the world or its troubles, but rather as a

challenge to serve Christ faithfully in the midst of whatever trials and

upheavals may be occurring around us or to us.

As far as the author of Revelation was concerned (and the members of

“the 7 churches of the province of Asia”), following Jesus was risky business. To be a disciple of Christ was to be, at

best, inconvenienced and at worst, put to death. The fact is, facing opposition is a given for

a follower of Jesus. Perhaps for us,

this will never take the form of violence; but the resistance that we face is

more subtle and maybe even more dangerous – that of the omnipresent lure of

simply letting go and allowing ourselves to drift with the current of our

society’s godless attitudes and behaviours (which often enough, is not overtly

“evil”; rather, it consists of a self-centred lifestyle which eclipses any need

to look beyond the satisfaction of my desires in the present moment). Following Jesus in our Western world requires

constant, intentional, deliberate awareness of what our Lord asks of us – are

we ready to be inconvenienced as we await – and work towards – the realization

of the Creator’s dream of a new world?

[1] Believed to have been the first Pharaoh. This “divinization” of the rulers of empire

would continue throughout the ancient world, culminating in the “apotheosis” of

Roman emperors upon their death (their inclusion in the pantheon and their

becoming the object of worship). Indeed,

in the Eastern part of the Roman empire, it was common for the emperors to be

worshipped as divine during their lifetime.

This pagan tendency to make a god out of the person at the pinnacle of

the imperial hierarchy is radically undermined by the Incarnation of (the Word

of the true) God as Jesus of Nazareth, a powerless peasant, born in dubious

circumstances, whose early years were spent as a refugee in Egypt, and

who spent most of his life in a Galilean backwater that was despised even by

his fellow countrymen (cf. Jn. 1.1-18, 45-46).

The Bible is a collection of documents that are deeply subversive…

[2] Cf. the divine judgments on the world heralded by the 7 trumpets

and 7 bowls (Rev. 8—16).

[3] A recurring and significant number for Revelation – symbolizes

completeness, finality, perfection.

[4] Jesus is described as “the ruler of the kings of the earth” in Rev.

1.5, etc.

[5] 10th century B.C.

[6] Cf. the way that God is described in the book of Revelation as “the

one seated on the throne” (Rev. 4.2, etc.).

[7] Cf. Rev. 6.15-17 where the wrath of both the One seated on the

throne and of the Lamb is unleashed against the rebellious world.

[8] The king of Israel was often referred to as “Yahweh’s son”: 2 Sam.

7.14; Ps. 89.20, 26-29; cf. also Ex. 4.22).

[9] Quoted frequently in the New Testament, especially at the scene of

Jesus’ baptism (cf. Mt. 3.17; Mk. 1.11; Lk. 3.22; cf. also Ac. 4.25-26; 13.33;

Heb. 1.5; 5.5).

[10] This is a favourite verse of the book of Revelation (cf. Rev. 2.27,

etc.).

[11] I.e. son of the divine Julius Caesar, his adoptive father and

predecessor, who had been apotheosized by the Roman senate following his

assassination.

[12] There seems to be a deliberate “non-violent hermeneutic” being

utilized by the NT authors as they quote the Hebrew Scriptures. Ps. 2 is one of the most frequently quoted

Psalms in the NT to refer to Jesus’ messiahship (cf. the voice from heaven at

Jesus’ baptism, Ac. 4.25-26, passim). Interestingly, Revelation is the

only NT book to quote Ps. 2.9 (Yahweh’s anointed will rule the nations with a

“rod of iron”; cf. Rev. 2.27; 12.5; 19.15).

Also, Luke omits Is. 61.2b (“the day of vengeance of our God”) as he has

Jesus read from the scroll of Isaiah in Lk. 4.17-19.

[13] Another title claimed by the Caesars.

[14] A term used by the Romans to herald a military victory or the

enthronement of a new emperor, both situations being believed to result in

“peace”..

Comments

Post a Comment