“Eavesdropping on Jesus” (22 Nov 20: Matthew 25.31-46)

May the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be pleasing to you, Oh Lord, my rock and my redeemer.

“Eavesdropping on Jesus”

(22 Nov 20: Matthew 25.31-46)

If you had the chance to travel back to

any point in time, when would you go? Would it be to New

Year’s Eve, 1999? …1989 Berlin? …1969 Woodstock? …1969 on the Moon? …1789

Paris? …1759 Québec City? …1517 Wittenberg? All of these moments

would seem strange to us, but at least the events that occurred at these times

are considered important to Westerners. But how if we

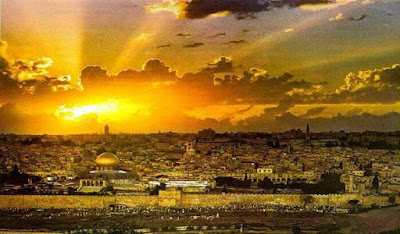

were to travel to the distant past to a part of the world where the culture is

extremely different from our own? How about the capital of the Roman

province of Judea around the year 30 AD? As we seek to understand

today’s Gospel, I invite you to accompany me on a journey back in time to the

turbulent, mysterious and intriguing world of first-century Jerusalem.

Today’s Gospel is the end of

a long conversation between Jesus and the disciples. Actually, it’s a really long response on the

part of Jesus to a question that the disciples put to him at the beginning of

chapter 24. Ever since Jesus arrived in

Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, he has been spending his days in the Temple. On Wednesday afternoon of Holy Week, Jesus

leaves the Temple for the last time, and his disciples contemplate the beauty

of the sacred buildings as they head down into the Kidron Valley. Jesus

remarks gravely:

“…not one stone will be left here upon

another; all will be thrown down…” (24.2)

Once they reach the summit of the Mt. of Olives, across from the Temple mount,

The disciples ask: “…when will this

be? and what will be the sign of your coming and of the end of the age?”

(24.3: NRSV)

With historical hindsight, we can give a straightforward answer – to the

first half of the question anyway. Almost

precisely 40 years after Jesus spoke these words, in the year 70 AD, the Romans

did indeed destroy the Temple and the city of Jerusalem. But it’s

the second half of the disciples’ question that is tricky: “…and what will be the sign of your coming and of the

end of the age?” (24.3: NRSV). At this point, we realize,

perhaps with horror, that we have wandered into a theological

minefield. Indeed, “the end times” has always been a source of

fascination and controversy among Christians.

Many believers have attempted – and

continue to try – to predict the moment of Jesus’ return (Mt.

24.36 notwithstanding). American preacher Harold Camping predicted

in 2005 that “the rapture” would occur on May 21st, 2011 and that

the world would come to an end 5 months later on October 21st. In

the months leading up to that date, teams of Camping's followers went across

the world to warn people to convert before it was too late. I came

across the Montreal team one day as I was walking down Ste-Catherine

street. After an interesting conversation with a young man who had been

recruited into the group only a few months previous, I asked him for his e-mail

address and promised to write him on May 22nd (the day after

the rapture was supposed to happen). I did indeed write to that man,

encouraging him to find a church that practiced a less “ambitious” method of interpreting

Scripture. I’m still waiting for a response to that

email… As for Harold Camping, he passed away in December 2013, and

finally found himself in the presence of Jesus. I’m sure his

eschatology has now been straightened out. Now, I realize that I’ve

opened a can of worms by mentioning the word “rapture”. If anyone

wants to further discuss that idea some other time, I would be happy to have

that conversation, as long as it’s not by email.

But what did the disciples mean when

they asked: “…when will this be, and what will be

the sign of your coming and of the end of the age?” The

KJV translates the Greek word “aion” here as “world” – “the end of the

world”. It used to be fashionable for biblical scholars to point out

that Jesus had made a mistake similar to that of Harold Camping – he had

predicted the end of the world within a generation of his death and obviously,

this didn’t happen and the world has continued to rumble on for 2,000 years

since Jesus’ time. However, it was the scholars who were

mistaken. First-century Jews like Jesus and Paul and all the rest

didn’t believe that at “the end”, the world would disappear in a puff of

smoke. No, first-century Jews were waiting for the end of “this

present evil age” and the beginning of “the age to come”. As early

as the prophet Isaiah, we find the concept of a “new creation” (cf. Is.

65-66). Despite the fact that the early Church quickly became a

predominantly Gentile community, the biblical and Jewish idea of the “age to

come” made its way into the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed (381 AD), which

ends with the words: “We look for the resurrection of the dead and the life

of the world to come”. So, it wasn’t Jesus who had

proffered a false prophecy; it was the scholars who had failed to understand

what Jesus/the disciples meant by the “end of the age” (cf. Mt. 28.20).

So, the disciples weren’t asking

about the end of the space-time universe. What they – and most of their contemporaries –

were hoping for was for the arrival of the Age to Come, for the kingdom of God

to replace the pagan kingdoms of this world, for Israel to be delivered from all

the Gentile empires that had oppressed her ever since Jerusalem had been

destroyed by the Babylonians and the people had been exiled in the 6th

century B.C. The hope of the disciples

was the same as that of Daniel, who had been taken to Babylon all those

centuries before and had had a dream of monsters crawling out of the ocean to

attack the people of God until “one like a son of man” is exalted and comes on

the clouds to the Ancient of Days and is enthroned beside him and then the

monsters are judged and destroyed and the “people of the saints of the most

High” are given an everlasting kingdom (Dn. 7, esp. vv. 13-14). Daniel’s vision of the vindication of the son

of man and his people after a period of suffering at the claws of the imperial

beasts sustained the people of God during the long centuries of pagan rule, and

also led, like now, to much speculation about exactly when Daniel’s

dream would come true and how the people of God should best prepare for that

day. When will the son of man be exalted

on the clouds of glory, when will we be set free from our pagan oppressors? When will the final judgment occur and God’s

people be justified over against the Gentile nations? When will justice finally be served? All this, and more, is contained within the

disciples’ question: “…what will be the sign of your coming and of the end

of the age?”

During “Holy Week”, Jesus stayed in

the village of Bethany at the home of one “Simon the leper” (21.17;

26.6ff). Every morning, Jesus would leave Bethany, make his way down

the Mount of Olives, across the Kidron Valley and up onto the Temple

mount. Every day, crowds of pilgrims gathered to witness Jesus’

debates with the religious leaders (21.17-18, 23). All these people

had come to the capital to celebrate Israel’s national holiday (i.e. Passover),

and by flocking around Jesus, they prevented – for the time being – his arrest

by the temple authorities (21.46). Each evening, Jesus left the

Temple, went back across the valley, up and over the Mount of Olives and

returned to Bethany.

On Wednesday evening, on their way

back to Simon’s place, Jesus and the disciples stopped at the summit of the

Mount of Olives in order to have a conversation before returning to Bethany for

supper (26.6-13). Jesus tells today’s

story during the darkest hours of his life – within 24 hours,

he will be arrested and within 48 hours, he will be dead. We can

imagine Jesus and the disciples snuggled amid the olive groves as the sun

dipped below the Jerusalem skyline and cast cross-shaped shadows on the spires

of the Temple. Let’s try and catch the tail-end of their

conversation (24.3)…

Imagine the bleating of sheep interrupting Jesus as he addresses the

disciples. Look over there! It’s

a shepherd leading his flock into a sheepfold next to the olive grove and

separating the goats from the sheep. (It is still customary in the

middle east to shelter goats inside, while sheep are more resistant to the

elements and can be left outdoors overnight).

DISCLAIMER: despite what our first

impression may be, the story of the sheep and the goats is far from being a

straightforward passage to interpret. There are some serious

brain-twisting issues in this story. Here are a few I’ve noticed:

1. “the coming of the

son of man in glory”: what does this refer to? The easy answer is “the second coming of

Christ”. The liturgical calendar demonstrates that

traditionally, the Church has indeed understood what Jesus tells the disciples

here as referring to “the end times” (in our future). Liturgically

speaking, today is New Year’s Eve. This is the last Sunday of the

Church year and next Sunday marks the beginning of the season of

Advent. Advent has a double meaning for the

Church. First of all, Advent is the season when we travel

backwards in time and join God’s people during the era before Christ,

and, together with them, we await the birth of the Messiah at Christmas.

However, Advent also has a second meaning – as the people of

God AD, we are also looking forward to a future event, i.e.

Christ’s Second Advent, his return to judge the living and the

dead and to consummate his endless kingdom. The structure of the

Church's calendar encourages us to see in these Gospel passages references to

the second Advent.

However, this interpretation is not without difficulties, or at the very

least, needs to be nuanced based on an understanding of the first-century

Jewish hope:

a. We have already seen that

the disciples are concerned with the destiny of Israel and that Jesus responds

to their concern by talking about “the coming of the son of man”. However we interpret this phrase, we must

take into account the context, which is Jesus’ prediction of the destruction of

the Temple within one generation and the disciples’ concern to prepare

themselves for this event.

b. In chapter 10, Jesus had

sent out the disciples two by two and told them: “When they persecute you in

one town, flee to the next; for… you will not have gone through all the towns

of Israel before the Son of Man comes” (10.23; cp. 10.16-23 with

24.9-14 – “the one who endures to the end will be saved”). The

disciples will not complete their mission to Israel before

“the son of man comes”.

c. In chapter 16,

following Peter’s confession that Jesus is the Messiah, Jesus tells his

disciples: “…there are some standing here who will not taste death before

they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom”

(16.28). Some of the disciples will witness the “coming of the son

of man” in their lifetime.

d. In chapter 24, Jesus

predicts the desecration and destruction of the temple, accompanied by the

“coming of the son of man” and says: “…this generation will not pass away

until all these things have taken place. Heaven and

earth will pass away, but my words will not pass away” (24.15-35).

Indeed, there are other possibilities for interpretation. How

do we square Daniel 7.13-14 & Is. 13.10, which Jesus quotes in Mt. 24.29-30

(cf. 26.64) with the long-standing second-coming

interpretation? Then again, where does the son of man go from

and where is he coming to? Should we interpret this phrase

literally? Or perhaps there is some symbolic, theological,

apocalyptic meaning? …food for thought.

2. Who are “all the

nations” (the sheep and the goats)?

3. Who are “the least of

these who are members of my family”?

4. Since when is final

judgment – eternal punishment or eternal life – based on whether one has

performed the “works of mercy” (feeding the hungry, etc.)?

1. “the

coming of the son of man in glory”: what does this refer to?

I’m going to have to leave this question

hanging. Once again, if you want to pick this up with me later, it

would be a pleasure.

2. Since when is final

judgment – eternal punishment or eternal life – based on whether one has

performed the “works of mercy” (feeding the hungry, etc.)?

Surely judgment is based on faith in

Christ or the lack thereof. It seems like this passage does not quite

sit comfortably with our theology. It must be pointed out that Jesus

is simply illustrating the classic Jewish concept of the final judgment, with

the righteous receiving eternal life and the unrighteous inheriting eternal

condemnation (cf. Jn. 5.29). However, Jesus is subverting the usual

criteria for judgment, i.e. observance of the mosaic law/maintaining ritual purity. According

to Jesus, taking mercy on “the least of these” weighs more in the balance than

adherence to the ritual minutiae of the mosaic law (cf. parable of the good

Samaritan: Lk. 10.25-37).

3. Who are “all the

nations” (sheep and goats)?

Are these disciples of Jesus, or

non-believing Jews or pagans or a combination? The phrase in Greek

is “pantha ta ethne”. It only occurs 4 times in Matthew and

each time, it refers to all the Gentile nations of the

world. In 24.9, 14; 28.19 it clearly refers to the nations towards

which the disciples’ mission will be directed.

4. Who are “the least of

these who are members of my family”?

As I was preparing this homily, I started

chatting on Facebook with a military chaplain colleague of mine who is a

Jewish Rabbi. He’s one of those rabbis who reads the New

Testament. I find that he understands the NT at a level that most

Christians rarely attain because he is steeped in the Jewish mindset, culture,

Scripture and tradition. My friend “gets” what Jesus is up to as a

first-century Jewish prophetic figure. I asked him what he thought

of this story of the sheep and the goats, and he replied that it seems to indeed

refer to the messianic age and is a typical Jewish story of the ultimate

destiny of Jews, on the one hand, and the goyim, i.e. the Gentiles,

on the other (cf. Mt. 13.24-30, 36-43; 13.47-50). So, it appears

that this is a story of the judgment of the pagan nations according to how they

have treated, not simply Jews, but those members of the renewed Israel that

Jesus is forming around himself, and in which Gentiles are welcome to become

members; indeed, they may have a faith greater than that of the “ethnic”

members of God’s people (cf. Mt. 8.10-12). In Mt. 12.50, Jesus says:

“whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and

mother”. Jesus insists that his true family are not those to whom he

is related biologically, but rather those who follow him. “The

righteous” (the sheep) are those Gentiles who care for those followers

of Jesus (predominantly Jewish) who experience persecution (mostly

from fellow Jews, but also from pagans; cf. Acts of the Apostles) for

their allegiance to Jesus (cf. 24.9-14, esp. v. 9).

I believe that this entire

section of Matthew’s Gospel is a challenge for us concerning our priorities

as Christians, and indeed, a challenge to correctly discern what the Christian

life is all about and how we should attempt to follow Jesus. Often, we get into trouble because we ask the

wrong questions. Like the disciples, we often

seek to get some kind of edge, some kind of insight into what’s going to happen

in the future, so that we can come out on top, or at least not suffer too much

when disaster strikes. The future is a

frightening thing, and we try to remove as much of the mystery from it as we

can. I mean, who could have foreseen at

the beginning of Advent 2019 what this year would bring? We have an instinct for self-preservation – for

staying alive yes, but also for maintaining our reputations and keeping our sense

of status and significance intact. At

the beginning of the book of Acts, the disciples ask Jesus a similar question

to the one we’ve been considering today.

As it turns out, this question was also put to Jesus on the Mt. of Olives,

40 days after the resurrection (Ac. 1.3, 12):

“…they asked him, “Lord, is this the time when you will restore the kingdom to

Israel?” He

replied, “It is not for you to know the times or periods that the Father has

set by his own authority” (Ac. 1.6-7)

As is the case with today’s Gospel, Jesus here responds, not by giving

the disciples an “end of the age” calendar, but rather by sending them on a risky

mission to make disciples in a dangerous world (1.8; cf. Mt. 10.16-25; 24.9-14). We must remember that all of the events

described in the book of Acts – the beginning of the Church’s mission – occurred

under the shadow of the impending doom that would befall Jerusalem, that the

disciples began to preach the gospel in the city where power was held by those

who had murdered Jesus and they then continued to preach outside the

familiar confines of the Holy Land in the wide world of imperial idolatry/violence/corruption.

However, at this point, 40

days after the resurrection, and before embarking on the mission which would

begin at Pentecost, the disciples still have a self-referential, inward-focused

approach to what it means to be the people of God – “is this the time when

you will restore the kingdom to Israel?”

In other words, we’re the people of God, the promises were

made to our ancestors (and to us), we’ve been suffering for

a long time, we’re fed up, it’s about time that things started to go

better for us. Jesus then proceeds

to expand the disciples vision, to raise their eyes from looking as it were,

through a microscope, to obsess over the fate of their own nation, to

looking as it were, through a telescope, to wonder at the extent to

which the love of the Creator reaches to the “uttermost parts of the earth” (1.8). The only consolation that the risen Jesus can

offer to this ragamuffin band is the assurance of his presence, the

power of his Spirit and the unfailing love of his Father. But isn’t that enough? As Paul said:

“I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the sharing of his sufferings by becoming like him in his death, if somehow I may attain the resurrection from the dead.” (Phil. 3.10-11)

What is especially striking about today’s

Gospel is the way in which the King, i.e. Jesus, identifies himself with

“the least of these”. Remember what the risen Jesus said to Saul

of Tarsus on the road to Damascus: “Why are you persecuting me?” Whatever

is done to a follower of Jesus is done to Jesus himself. This

is an intimacy with Christ that we experience every waking moment but can

only begin to understand this side of

eternity. When we suffer as a Christian, Christ suffers in us and

with us. The book The Hiding Place chronicles the story

of Corrie and Betsie Ten Boom, Dutch Christians who sheltered Jews in their home

during the Nazi occupation of Holland. Eventually, they were

arrested by the Gestapo and sent to a concentration camp. Upon

arrival at the camp, they experienced the first of a long series of

humiliations – they had to strip naked and shower in a large room with all of

the other prisoners; they also had to use the drain holes in the shower room as

toilets. As they shivered under the cold water, Corrie said to her

sister, “They took his clothes too”. Betsie would

eventually die in the camp, shortly before the end of World War

II. Corrie was released due to a clerical error and spent the rest

of her life travelling the world as a “tramp for the Lord”, preaching a gospel

of grace, healing and forgiveness. Corrie & Betsie were

recognized as being “righteous among the nations”, a distinction awarded to

Gentiles who helped save the lives of Jews during the

holocaust. This phrase – coined by the organization Yad

Vashem (“a monument and a name”; Israel’s official memorial to the

victims of the holocaust) fits well with today’s

Gospel. Interestingly, there is no equivalent award for Jews who

saved fellow Jews during the holocaust; they are seen as having simply done

what they were obliged to do for members of their own people.

Judaism recognizes Gentiles whose

behaviour demonstrates genuine love of neighbour as being

“righteous”. This notion of righteousness within Judaism can help us

better understand the “righteousness of Christ” that Paul speaks about in his

letters. As Christians, we claim that our unrighteousness was

imputed to Christ on the cross and that his righteousness was imputed to us

through faith. To live as a “justified” person, i.e. someone to whom

the righteousness of Christ has been imputed, is not simply to kick back,

secure in the knowledge that Jesus’ perfection has been credited to my

“morality account” and that I am destined for heaven. On the

contrary, those who have truly understood their justification will live as

“justice-people”, they will hunger and thirst for justice (cf. Mt. 5.6,

10-11). Mother Theresa saw Christ in those who were dying of leprosy

and loneliness in the gutters of Calcutta. As justified people, we

are members of Jesus’ family and are part of his purpose of making a new

creation, a world of justice and peace, a world where the Sermon on the Mount

is not a seemingly unattainable ideal, but simply the way things are.

Just as the “righteous” in the

Gospel are shocked at being identified as such, sometimes “the

righteous” of our own time are not to be found in the

churches. Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn says:

“Jesus instructs us to love, to seek the Divine in the everyday, to foment real

peace and real freedom, to share bounty among the poor, and to challenge

malevolent power even if it means placing yourself at great

risk. Now and then we run across a human being who actually does

that. They don’t always identify themselves as Christian”.[1]

It seems like the main challenge of

today’s Gospel concerns how we treat our sisters and brothers in Christ, those

fellow members of “the least of these”. We must practice radical

solidarity amongst ourselves. As Jesus said in John’s Gospel: “By

this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one

another” (Jn. 13.35). The world is looking for something real; we

must respond to this challenge because the credibility of the gospel we

preach depends on it.

C.S. Lewis: “There are no

ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere

mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations – these are mortal,

and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals

whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit – immortal horrors or

everlasting splendours. This does not mean that we are to be

perpetually solemn. We must play. But our merriment must

be of that kind… which exists between people who have, from the outset, taken

each other seriously – no flippancy, no superiority, no

presumption. And our charity must be a real and costly love, with

deep feeling for the sins in spite of which we love the sinner – no mere tolerance,

or indulgence which parodies love as flippancy parodies

merriment. Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbour is

the holiest object presented to your senses. If she is your

Christian neighbour, she is holy in almost the same way, for in her also Christ…

Glory Himself, is truly hidden.”[2]

As Henri Nouwen said,

“Life is Advent; life is recognizing the coming of the Lord”. We

must recognize Jesus in the faces of those who are in need of hope – those who

are mourning the loss of a loved one, those who are depressed and who are

expecting to spend another Christmas alone. Lord, open our eyes to

recognize you in each others’ eyes.

“O divine Master, grant that we may not so much seek to be consoled as

to console, to be understood as to understand, to be loved as to love. For it

is in giving that we receive, it is in pardoning that we are pardoned, and it

is in dying that we are born to eternal life.

Amen.”

[1] Bruce

Cockburn, Rumours of Glory: A Memoir, Toronto: HarperCollins, 2014,

p. 41.

[2] the ending of

C.S. Lewis’s sermon “The Weight of Glory”, preached in the Oxford University

Church of St. Mary the Virgin on 8 June 1941 [in the middle of WW II].

Comments

Post a Comment